By Tara Cavanaugh

Starting over: the idea carries a certain romantic stigma. It’s the idea of moving someplace new, of beginning a more satisfying career, of being fresh and full of promise and hope.

It’s easy to forget that starting over is a process of re-construction, requiring resources, confidence and a lot of work.

The Ann Arbor Public Schools Adult Education program is a place for re-construction, providing the resources and confidence to the adults who need to finish their high school education. The self-funded, multi-layered program provides hundreds of area adults each year with the chance to create the educational foundation they’ll need for the rest of their lives.

Confidence, confidence, confidence

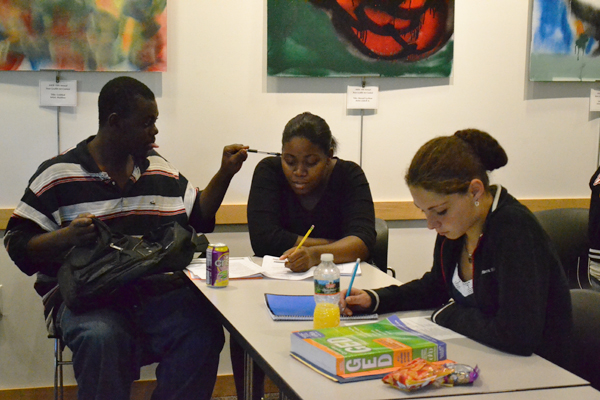

Each Wednesday afternoon, the large side room in the Mallets Creek library is home to one of the Adult Ed GED prep classes. Inside are two teachers and a variety of students. Some are young, in ripped jeans and sweatshirts. Some are older, in plaid button-downs.

They’re all working hard to build the skills they need to graduate with their GEDs.

Georgio Scott is a young father who attends the Adult Ed program with his fiancée. “We’re just trying to graduate, trying to get to the next step,” he said. “Everything in the world we need a GED for.”

Scott and his fiancée have an 18-month-old daughter. “She’s something else,” he said bemusedly. “She’s walking –– no, running. We’re trying to potty train her now. She’s just learning to say ‘pot-pot.’”

Scott said he was close to graduating high school in Ypsilanti when he dropped out, having earned 19.5 of the 22 credits he needed. Since then he’s felt the pressure of trying to provide a good home for his growing family (his fiancée is pregnant again). They’ve couched-surfed for the last year and a half, even staying in a shelter at times. And taking care of a toddler is expensive: “I went to the store and bought diapers for like $7 today,” he said. “She goes through a 20-pack in 3 days.”

Despite all this, Scott is cheerful, confident and clear-eyed. He said when he gets his GED, he’s going to college to become an engineer. First, though, he’s finally getting more comfortable with math, thanks to Larry Fitzpatrick, one of the teachers. “Larry said to me: If you don’t like math, I guess you don’t like money. I said, Yes, I like money!” Scott laughs.

“In the end, I know this will pay off.”

Randy Bostic also knows his Adult Ed classes will pay off. Bostic worked for a company called Ultra Air for 18 years, until the plant he worked in was shut down and moved elsewhere for cheaper labor.

He’s licensed in refrigeration, meaning he’s experienced in working with compressed air driers. He’s also worked as a net assembler in fabrication and welding, what he describes as “building the machines from the bottom up.”

He’s been out of work since 2009. “I have a lot of skills, but without a GED, nobody wants you,” he said.

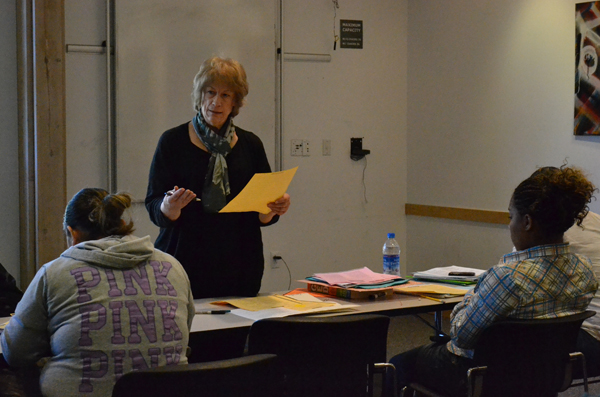

Bostic has attended the program on and off for a few years. It’s an arc most students follow, said Beth Carlson, one of the program teachers.

“Many of our students start, stop and come back a year later and start again. A lot of that has to do, hopefully, with employment. It’s just the struggles of that level of poverty. It’s hard,” Carlson said.

“So many of our students struggle with life. Who’s going to take care of the kids? For those who do drive: Do I have gas to get to class next week? And if you’re doing an entry level job, your employer isn’t always anxious to let you out in the middle of the day to go to class.”

To be helpful to as many people as possible, the program has become extremely flexible. Director Sharman Spieser calls the program –– with its long registration periods, free classes and willingness to take new students any time and without residential requirements –– the most accessible adult education in the area.

While Scott is full of cheerful confidence, Bostic is resolute. “It’s taking me a while, but I’m not going to give up,” he said firmly. “I’m not going to give up until I get that GED. I will graduate.”

Scott and Bostic are quite different. One is young, one is middle aged. One is black, one is white. One wants to start his career, while the other is hoping to restart his. But they both are determined and confident that they’ll get where they need to go.

That confidence is helping them get through the program no matter what hurdles pop up –– and that confidence is key to the program’s success, said director Sharman Spieser. “In Adult Ed, we can’t tell you when you’ll be ready to pass the test, but we can tell you that you will be ready. And we’re not going to kick you out because you haven’t passed it in a semester or a year.

“For so many of our students, the reason they didn’t succeed in school was because they didn’t feel comfortable,” Spieser said. “They were labeled, or they moved a lot, and so when they come into our Adult Ed program, our top priority is showing them respect and letting them know clearly and unmistakably how much we value them, and that their potential is unlimited.”

Once they achieve that feeling, she adds, they don’t want them to lose it.

Scott, Bostic and other students say that the program’s teachers are different than the ones they had in K-12, noting that they’re more accessible, patient and flexible. “They’re more down-to-earth,” Scott said. “they want you to go at your own pace.”

Carlson points out that the students are different. “Other than a grade or parent approval, when you’re a kid you can’t see where school is leading you. By the time you’re an adult, you see what you missed and why you need it today so badly,” she said. “It’s a different perspective.”

Spieser also points out that the environment is different, providing the flexibility to accommodate students’ circumstances. She says it’s an ultimate mastery learning place, where students keep working until they’ve mastered the material.

No matter the exact reason –– the teachers’ style, the students’ determination, the learning environment, or, more likely, a combination –– the program is increasingly successful. Last year it graduated 55 students, a jump from 40 graduates two years prior.

Big cuts, big growth

Spieser joined the district five years ago as the principal of A2 Tech, which was responsible for Adult Ed at the time. But the school lacked a GED program due to severe state budget cuts to adult education programs. Current funding for such programs is about $22 million from the State School Aid Act; in the 1980s, it was $400 million.

“But I said, We have to have GED. At the time we were the only free program in the county, or one of them,” said Spieser. So she scraped together money for one basic GED prep class and ran it in the church next door with one teacher.

Since then, the program has blossomed into what Spieser calls “a rich and layered service.” There are two new classes this year although Spieser didn’t add any staff. And although there are official enrollment periods, new students are still accommodated year-round.

“It’s my philosophy that if someone wants to reconnect with learning and education, you need to let them do it the moment when they want to,” Spieser said. “Because that’s when their life situation allows for it, and they’re the most motivated.”

The multi-layered program is now self-sufficient, thanks to a careful combination of grants, partnerships, and planning. The federal Workforce Investment Act and No Worker Left Behind Act provide grants. The University of Michigan Hospital and the Washtenaw County Jail pay for Adult Ed to run classes in their facilities. And part-time teachers, who are already retired and have a cap on their salaries, make up most of the program staff, which helps keep costs low.

“It’s not wildly different from a program that you would have seen 15, 20 years ago,” Spieser said. “But given the devastation that adult education has had in our state, now everybody’s trying to come back. There are some programs that have had to close because of a lack of funding.”

Although Adult Ed is no longer a part of A2 Tech and is completely self-sufficient, Spieser is grateful that the district still helps out with unseen costs, such as doing payroll and providing classroom space. “They support us unequivocally,” she said, “but they don’t need to support us financially.”

Learning while on lockdown

Twice a week, Adult Ed teacher Larry Fitzpatrick teaches supplemental math at the Washtenaw County Jail. Getting to class at the jail takes a little more effort than going to the library or A2 Tech.

“There’s doors closing behind you all the time,” Fitzpatrick said. “They’re locking, and there’s bars, and you have to get buzzed in at each door and you have to have some kind of ID.

“You know that you’re coming into a different environment.”

But Fitzpatrick insists that it’s merely a different environment, not an intimidating one. His students are accused or have been convicted of crimes, and are either awaiting trial or release or on their way to prison. The jail is a short-term facility, and the three GED teachers have to quickly establish relationships with their students. And that’s what they do.

“I don’t care why they’re here,” Fitzpatrick reasoned. “They’re in my classroom. They’re my students and I want to help them.”

He works to bolster his students’ confidence, same as he does with the students outside of the jail.

“What I tell them all the time is: Now you are an adult learner. Which means that you have more experience, you have more skills, you’ve done more things, you’ve taken care of yourself, you’re used to paying your own bills,” Fitzpatrick said. “So when you come back into a learning environment, don’t think you’re coming back in the fifth or sixth grade. Just because you had difficulty with math then doesn’t mean you’ll have difficulty with math now.”

Facing the future

As the program gives students hope for their futures, it faces some difficulties of its own.

The current GED test will change in January 2014, and will only be given online. The GED test is made up of five separate tests, and students often spread them out, taking and retaking tests as needed. But the January 2014 change presents a deadline for all students currently working on attaining their GED: finish your tests before then, or start over again with an entirely new set of tests.

The online course will also cost more, and Spieser worries that the program will have to pass those added costs onto students. Currently the program pays the testing fees. Spieser says the state has been unclear as to whether it will help the Adult Ed programs pay the increased cost. Still, the program does everything it can to be affordable and accessible to all adult learners in the community.

Because of the upcoming changes, Spieser is encouraging students to finish their GED tests by December of this year. “Anyone who has started the program needs to finish it,” she said. “We want as many people as possible to have their GED before December.”

The new test also means changes for the program itself. Staff will need to be trained in the new curriculum. And computer literacy will have to be taught with a greater focus, because the new online-only test might pose difficulties for students who don’t have a computer at home. Spieser says the program is working on purchasing more computers for classroom use, and hopes to have the budget for additional instructional materials for the new test.

The program usually doesn’t run in the summer, but this year will be different. There will be comprehensive GED classes in July and August. Registration information will be announced in the spring.

In the past five years, all changes Spieser has made to the program have helped it reach more students, no matter their circumstances. Spieser is concerned that the changes the program has to make in order to accommodate the new test will affect its accessibility.

Despite the challenges ahead, Spieser and the staff are committed to keeping the program accessible.

Fitzpatrick puts it this way: “It’s a very valuable program, for the fact that it catches a lot of students from many areas and gives them a chance to reconnect with education. It’s a real benefit to the community as well as to those adult learners we serve.”

Related stories

- Important GED deadline coming soon

-

Photos: A2 Tech and Adult Education graduation at Washtenaw Community College

1 Trackback / Pingback