By Tara Cavanaugh

Sometimes, a few small changes can make a big difference.

That’s what Mitchell Elementary and Scarlett Middle schools are showing as they implement new school-wide approaches that improve teacher instruction, student behavior and social skills.

At Mitchell, the approach is called Responsive Classroom. At Scarlett, it’s Developmental Designs. The sister programs, developed by the nonprofits Origins and the Northeast Foundation for Children, foster social and emotional learning by empowering students, developing student responsibility, and giving teachers new classroom management tools.

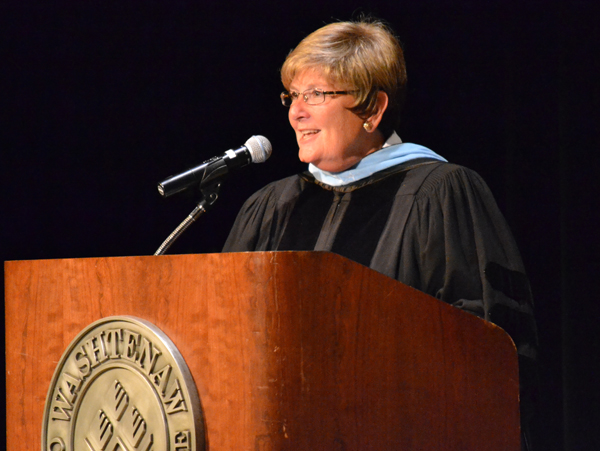

“It’s connected to Superintendent Dr. Patricia Green’s plans for the district,” said Mitchell Principal Kevin Karr. “As we go through the next few years, understanding how to address the discipline gap, we think that the Responsive Classroom approach is going to be a big part of that.”

“If we take seriously the idea that schooling is about both social and academic development, then we need to figure out what we are teaching about social development,” said Dr. Cathy Reischl, a clinical associate professor of education at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Reischl coordinates the Mitchell-Scarlett Learning Collaborative with the University of Michigan School of Education. In developing the partnership between the schools and U-M, Responsive Classrooms and Developmental Designs were chosen to help create what Dr. Reischl calls “K-8ness,” or a continuum between the two schools. The School of Ed is now helping the schools implement the approaches seamlessly school-wide.

“The approaches help us say: there is a social curriculum,” Dr. Reischl said. “It is learning how to be fully involved in each others’ company –– being in relationship with each other and also in growing our conceptual knowledge during the day.”

Small changes in thought and language lead to big changes in learning

A piece of conventional wisdom is that thoughts shape actions. So could a teacher’s thoughts shape student actions?

In both Responsive Classroom and Developmental Designs, the answer is yes.

“If the student lineup is not working, if that transition is a problem, it’s probably because I didn’t practice it enough with the kids and we need to make time for it,” said Beth McCready, a third grade teacher. “So instead of being frustrated, I just think, I need to practice it again.”

“Even though it seems like students should know all those things, we don’t expect them to be able to do it until we’ve taught them specifically,” Karr said.

Responsive Classroom and Developmental Designs encourage teachers to make small tweaks to the language they use with students.

“A teacher could say, ‘I see that all the backpacks and coats are put away neatly. I see that all the boys and girls have put their things in the lockers and that the lockers are closed. Wow, that’s great.’” Karr said.

“So that really says to kids, that’s what we’re supposed to do, and my teacher taught me previously to do this.”

With the approaches, teachers know it’s necessary to remind students what acceptable behavior looks like, Dr. Reischl said. Without meaning to, teachers can spend more time telling students what not to do instead of what to do.

“We say a lot of ‘Be quiet’ rather than: ‘Your job right now is to be choosing a book and sitting and reading it quietly,’” Dr. Reischl said. “Or instead of saying, ‘Stop running!’ you should just say, ‘Walk!’”

This focus on language represents a slight shift in thinking for some teachers. McCready said she feels this year that she’s taking more ownership of her behavior with her students. By allowing the students to make decisions about their rules and learning, she’s also allowing them to take more ownership of their behavior too.

“Academically and socially they’re taking more ownership of what they’re doing,” McCready said. “And they like it. They like having that power and that control.”

Teachers are also encouraged to use specific behavior when helping students learn.

“Sometimes with teachers –– and I’m certainly like this –– we’ll say, ‘You did a really good job!’” said Principal Karr. “That’s a really nice thing to say, but that’s less meaningful than: ‘I really like how, when you wrote your essay, that you remembered to put in the introductory paragraph.’ Now that’s something the kid is really grabbing onto.”

Language like this moves control from external to internal, said McCready. “A student is going to do the assignment because he wants to do well on it, not because he’s trying to impress me,” she explained.

“A lot of people believe that when they see a classroom running in this way that somebody is a ‘natural teacher,’” Dr. Reischl said. “I don’t think we have natural teachers. We have people who have learned really solid practices that help all kids know how to fully participate. And that’s professional knowledge.”

Smooth systems

One morning in early October, music teacher Dan Tolly wrapped up a class calmly and swiftly. So did the students.

“You are standing up,” he said gently, and the twenty-five students landed on their feet. “You are turning to a partner.” Each student turned to face a partner.

“You are putting your hands on your partner’s shoulders. You are talking about the best thing in music class today for the next 30 seconds.” Quiet chatter ensued.

The talking stopped as soon as Tolly spoke again. “You are turning to the map wall.” All students turned to the wall near the door. “And now you’re lining up to leave.” The students quietly formed a line.

“There’s a sense of calmness and engagement,” Principal Karr said, watching the class. “It’s predictable for the kids, and also for the teachers. This has all been taught in a systematic way.”

Starting off on the right foot

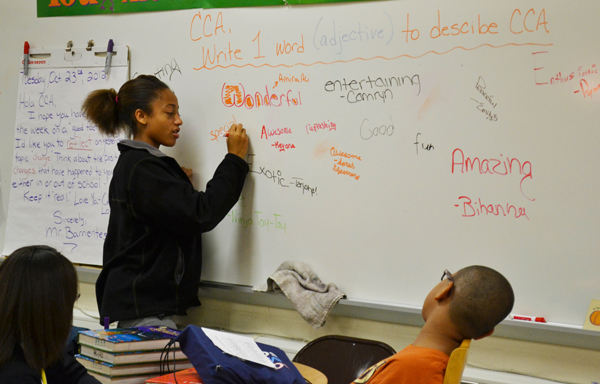

A week later at Scarlett Middle School, there’s a similar sense of orderliness in Salvador Barrientes’ morning CCA class.

CCA stands for “Creating Community through Advisory.” In this half hour class, students learn to respect each other by sharing, playing games, and making decisions together. The atmosphere is structured yet comfortable.

“Our community is very diverse –– economically, socially, racially,” said Gerald Vazquez, principal at Scarlett. “The experiences our kids come from are very diverse.”

“Some kids might be coming off the bus very angry for whatever happened at home. Some kids might not have any issues. But CCA stabilizes it for everybody. It gives them a chance to refocus, get in an environment where they feel supported.”

The CCAs will stay the same for the entire school year, with the hope that the students in them become mini-families.

“You start the day engaged in conversation, talking, positive, safe, and everybody’s in class,” Barrientes said. “Middle school kids tend to think if you don’t agree with them, you don’t like them. Now it’s much more of a sense of talking, having discussions, having disagreements if necessary, but that’s alright.

“That’s what I love about CCA. I have some very vocal children in here” –– he chuckled –– “but they can be that way and be comfortable with that.”

“It really starts the day in a way that’s quite different than the bell ringing and everybody starting to do math problems,” Dr. Reischl said. “You’re not going to disappear. You’re noticed, you’re named, you’re recognized as a member of the small community that’s coming together.

“I think we’re all in need of positive social interactions at the start of our days, especially when that sets the stage for really meaningful work that is promoting growth in people.”

During Barrientes’ CCA, the students talked about transitioning the CCA activities to three days a week instead of five. The entire school was working on making the transition, and classes were deciding how to spend the first half hour on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

“From how I see it, it’s really a constructivist view, letting the kids choose what they want to do so they’re invested in it,” Barrientes said. He took the ideas to a staff meeting the next day, where teachers talked about other students’ ideas submitted from their advisories.

Students stick to their own rules

In September, as the presidential election fomented discord between Republicans and Democrats, Scarlett and Mitchell students proved the success of a representative democracy.

The middle schoolers and elementary students each created their own set of rules for their school. Grownups provided some guidance and structure, but the rules were the students’.

Mitchell students made rules for their classrooms, and then sent representatives to meet with Principal Karr to share those rules. Those reps then picked grade reps, who pared down the many rules into a handful with the help of school staff. A similar process happened at Scarlett and also included an all-school assembly during which the student delegates explained the process and outcome.

Mitchell’s new rules are simple: Be responsible, be respectful, be safe and have fun.

Scarlett’s new rules, expressed in its new “Social Contract,” are also simple: Feel safe to express and be yourself, have a positive attitude, focus on the task at hand, and treat others how you want to be treated.

Creating school rules gave students an opportunity to determine how they want the school atmosphere to look, sound, and feel, said Gerald Vazquez, Scarlett’s principal. “Kids will tell you when they feel good in their environment.”

One new disciplinary tactic addresses what happens when students don’t feel good in their environments.

It’s called “TAB,” which stands for Take A Break. Middle students who don’t respond to visual or verbal redirection from teachers take a short break at a designated desk off to the side in a classroom.

The TAB is supposed to be quick, just one to three minutes, said Mark Sobolewski, a strategies for success teacher at Scarlett.

If a teacher determines a student needs more time for reflection, the student does a “TAB Out.” Each teacher has a partner, and the student goes to the partner’s class to the TAB Out desk, where they fill out a sheet that helps them reflect on their behavior.

The sheet asks questions such as: What choice was made resulting in you having to take a break? What choice can you make to have your needs met in a more appropriate way? Do you need to repair any damage to relationships to move forward?

“We have spent a lot of time modeling and practicing how to enter a learning environment from both ends,” said Sobolewski. Students understand how to enter another classroom quietly, and they also understand not to engage a student who enters the class to TAB Out. “We’re trying to give them as many opportunities for problem solving behavior before adults have to get involved.”

A similar procedure happens at Mitchell, and it’s called “Rest and Return.” There is a space for students to take a “time out,” and there is space in a partner teacher’s room as well. Sometimes students make the choice on their own to take a quick break.

“They realize, because they’ve developed a self-awareness, that they’re not regulating themselves,” Principal Karr said. “And because they’re not out of the classroom, they’re still engaged in what the teacher is doing.”

Karr likens the process to an adult taking a short walk or break during the work day.

“It’s a lot to ask of kids, expecting them to sit and learn and be focused for so long during a day. Some of our kids just aren’t able to do that,” he said. “In traditional settings, they got labeled as bad kids. But now we know, with social and emotional learning, that it makes sense that people need moments to stop and regroup. They do that in a variety of ways.”

A bright outlook

A few years ago, as the Scarlett-Mitchell partnership with U-M was being formed, all schools in the district were learning about implementing PBIS, which stands for Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports.

Now used across the district, it’s a form of social curriculum that stresses positive reinforcement, and it’s directly related to the Responsive Classroom and Developmental Designs approaches, said Erica Hatt, a fourth grade teacher at Mitchell.

Hatt was on a committee of teachers and community members dedicated to creating a cohesive K-8 curriculum, which helped form the Scarlett-Mitchell and U-M partnership.

Hatt said the Responsive Classroom and Developmental Designs approaches are their form of PBIS.

According to a research paper on the Responsive Classroom website and a fact sheet on the Developmental Designs website, the approaches are an effective form of PBIS. They establish a positive environment, reinforce positive behavior and establish a consistent response to inappropriate behavior.

The difference between the approaches and PBIS is reinforcement: PBIS allows individual schools to choose adult responses to positive behavior, whereas the approaches emphasize teacher language.

Addressing social and emotional learning is now considered an important key to addressing the achievement gap. A recent study from the University of Virginia in Charlottesville found that the Responsive Classroom approach leads to learning gains.

The study followed 24 elementary schools in a Virginia district that either received training, materials, coaching and administrative support or were part of a control group that did not use the program.

The study found that schools with high fidelity of the program –– that is, schools that made sure to implement the program as fully as possible –– reported significantly higher math scores.

Although changes in scores are hopefully down the road, Principal Vazquez can already see changes in his school.

“I think the most powerful thing we’ve seen is just how kids are treating one another in the hallways,” he said. “There’s a lot less nonsense. Our suspensions and referrals are significantly, hugely down.”

By how much? Vazquez estimates 75 percent.

“We knew the investment would pay off eventually,” he said. “I think if we’re honest, we didn’t anticipate this level of buy-in.”

The changes aren’t just on the student end.

“I think it’s changing the way we as a staff think about and talk about teaching and learning, and it’s bringing us closer together as a whole staff,” said McCready, sitting in her third grade classroom after school. “That’s something that’s been really powerful to be a part of.

“I think we have an effective staff here to begin with, that’s really, really committed to kids,” she added. “It’s nice to have a focus for that commitment that we’re all working together toward the same goals.”

Both schools have high hopes as they continue implementing Responsive Classroom and Developmental Designs. They have just begun implementing the approaches.

“My hope is two, three years from now we see that we’ve built a community of learners and a school community that really takes care of each other, and that we have a stronger community,” said Principal Vazquez.

“It’s been an encouraging start –– with hopes of a better finish.”

4 Trackbacks / Pingbacks