By Jo Mathis/AAPS District News Editor

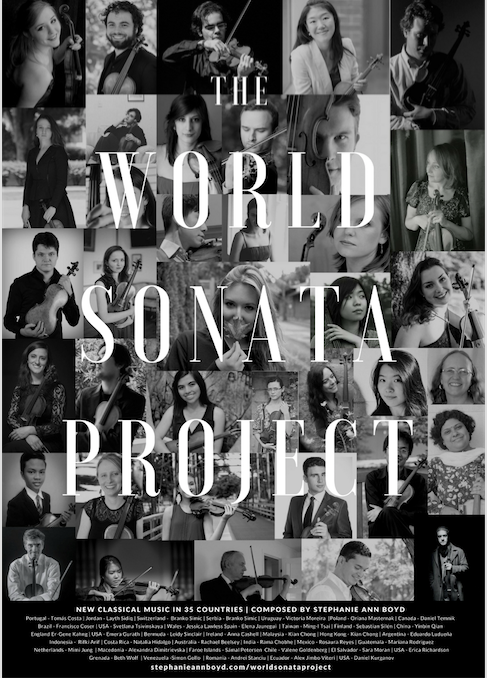

Those who attended Pioneer High School with Stephanie Ann Boyd will not be surprised to learn that the 2009 graduate has been commissioned to write a new solo violin sonata by violinists in 35 countries as part of the World Sonata Project.

After all, Boyd was the teenage violinist who brought her laptop to school solely for the purpose of composing music at lunchtime, and she’s the one who put together an extracurricular orchestra before her senior year.

This new World Sonata Project is a tribute to the memory of John Kendall, the Suzuki method pedagogue and former Ann Arbor resident with whom Boyd studied.

“He was like Yoda,” Boyd recalls, speaking via phone from her Manhattan apartment. “He was small and bent over and had a radical sense of humor and was the kindest person I know. He was so wise and brilliant, I’d literally take what he said and go home and write it in really large print on a piece of paper and stick it on my bedroom wall.”

She says he could recall the names of every student he taught over several decades all over the world.

After he passed, she felt guilty that she hadn’t given him as much as a student as he had given her as a teacher.

“Now that I’m a teacher, I realize that’s how it goes,” says Boyd, who is the 2017-2019 Composer in Residence for the Eureka Ensemble orchestra in Boston.

Commissioners of the new solo sonata, “Nostrorbis,” are performing their countries’ premieres of the piece over the course of 2017 and 2018.

These premieres and performances will happen in traditional concert venues but will also deeply impact audiences on an ambassadorship level in performances at national landmarks such as the Great Wall of China, at embassies, at a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, in Faroe Islands churches, and others.

A musical legacy

Boyd’s musical talents come naturally. Her father, Jonathan Boyd, played trumpet at Pioneer and was in the Michigan Marching Band. One of her uncles was a cellist while a student at Pioneer.

Another mentor was her paternal grandmother, Margaret Rages Boyd, a piano prodigy who lived in Ann Arbor for 60 years before moving to a home for seniors in Chelsea.

In fact, when people ask Stephanie what it’s like being a female composer, she says she learned all about that when she was a child.

“The first composer I knew was my grandmother,” says Boyd, who still speaks to her grandmother on the phone every day.

Perpetual purple pride

Back in the middle of her sophomore year in 2007, Boyd transferred from Rudolph Steiner School to Pioneer solely to join the celebrated Pioneer Symphony Orchestra.

“It was difficult but necessary, “ she says of the move from a school she loved. “I needed a Grammy-winning orchestra to be part of every day.”

She never regretted her decision.

Pioneer’s Director of Orchestras Jonathan Glawe says that as a student, Boyd stood out because of her enthusiasm, inquisitive nature, musicianship and work ethic.

“Her ability to follow through with lofty musical projects at a young age was inspiring to both myself and her colleagues,” he says. “As a composer, I find Stephanie’s music to be rich with imagination, full of unique musical textures, and also accessible for various levels of musician.”

He’s not surprised that her career as a composer has been reaching new heights.

“I consider Stephanie to be an important member of a new wave of up-and-coming composers who will make a big difference in the decades to come,” he predicts.

Boyd recalls that at that point, she was already completely obsessed with composition, and at the age of 17, wrote two symphonies, a ballet, and a violin concerto in the span of six months.

“Outside homework and practicing, it was all I did; it was all-consuming,” she recalls.

Andrea Yun, Jonathan Glawe’s predecessor, agreed to let Boyd do an independent study hour during her junior year. She still remembers sitting on the carpet of her office during second hour, back to the wall, writing.

“I remember running up to one of my friends in C Hall right before third hour, excitedly telling him that I had just written the first minute of my first chamber music piece,” she recalls. “Fantasia Olora for cello and piano has since become one of my most frequently played pieces, and it’s nearly a decade old now.”

During her years as a member of the Pioneer Symphony, there was always talk among the most gung-ho of the students of putting together some sort of extra-curricular orchestra. The summer before her senior year, Boyd finally got up the courage to send out emails to her friends, asking if they’d be interested in participating in an orchestra that she would conduct and that would play through her music.

“I summoned up even more courage and asked Jonathan if he would let me borrow the use of the music room after school one day a week,” says Boyd, who turns 27 today (Aug. 7). “What an incredible boon it was to me when Jonathan said yes, and told me to let him know if there was anything else he could help me with. I remember feeling so fortunate and truly a bit stunned to have run into someone who was endlessly generous, who was eager to pull out all the stops for someone who had a vision they cared about. “

Forty of the most talented musicians at Pioneer said yes to her emails. On some weeks they gave her four hours of rehearsal time.

“I learned so much from that time about leading people, about conducting, and about my own music,” she recalls.

While studying at Roosevelt University’s College of Performing Arts in Chicago, Boyd decided that she wanted to set up a composition residency to teach students how to write string quartets and work with a student orchestra on performing one of her pieces.

She wrote up an entire curriculum and proposal and sent it off to Glawe, who had just succeeded in the huge task of instituting a “Pioneer Orchestras at Interlochen” week during the summers.

He eagerly agreed to bring her on as composer in residence that year, and after dreaming about Interlochen for so many years as a teenager but never having the finances to attend, she finally got to take part in something even more meaningful than going there as a student.

As she puts it: “There’s nothing like coaching a string quartet through a rehearsal of 12 brand new pieces by 12 brand new composers who are all gathered around, hearing their own collections of notes for the first time, and there’s nothing like having the mega-orchestra that the Pioneer orchestras create when all three of them merge together playing your fantastical string orchestra piece; surround-sound basses—12 of them—playing your low melodies at the back of one of the most majestic outdoor concert venues in the U.S.” Since that summer she has taught private lessons to young composers from around the world via Skype.

She says that if the audience doesn’t have goose bumps from her music, she feels she hasn’t done her job.

“Hearing little kids coming out of my concerts humming my melodies: that’s incredible,” she says.

Boyd was delighted to get a call from Glawe about a month ago telling her that the Pioneer Symphony Orchestra will perform her “Beyond the Gate” for string orchestra when they present a concert at the prestigious Midwest Conference this December in Chicago.

“I wish I could tell those students to savor every single drop of orchestra class,” she says. “I wish they could feel the gravity of what can be incubated during those years with Jonathan’s support. I feel it nearly every day of my life, dwelling on my origins, holding steady to those roots while planning the trajectory of my future.”

The World Sonata Project

For Boyd, graduate school at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston was “absolute heaven.”

“It was so natural and so much fun and so uplifting to be around that kind of talent all the time,” she says.

After Boston came the move to Manhattan, which immediately felt like home and remains so today.

Boyd lives on the city’s upper west side near Lincoln Center, good bookstores, and classical music venues. Boyd has an “endlessly inspiring” assortment of friends from the music world as well as corporate.

Before taking on the World Sonata Project, Boyd wrote a violin sonata for a top violinist in each of the 50 states after reaching out to them via email, asking if they would commission that piece.

“For the most part, everyone said yes,” she says.

Now, it’s on to the world sonata—work she calls incredibly humbling. She has Skyped with violinists around the world and heard incredible stories.

She says when emailing, she sometimes uses Google Translate, as do those corresponding to her.

But it eventually gets down to that universal language.

“When we get to music,” she says, “we’ll be just fine.”

To hear Boyd’s favorites of her own work, including her recent violin concerto Sybil, click here.

Be the first to comment