Story and photos by Jo Mathis

AAPS District News Editor

When Tyrone Weeks was growing up on Detroit’s historic North End, his house was unique to others in his neighborhood because his father lived there.

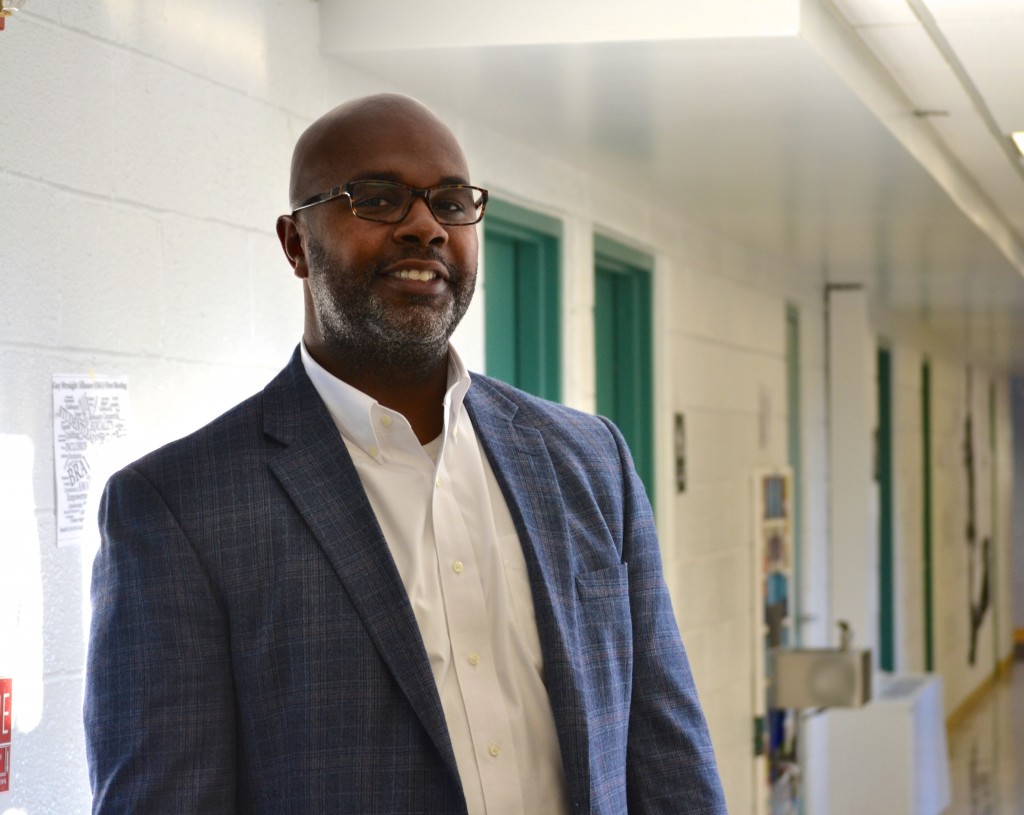

“This is not an exaggeration; I’m not embellishing: My mother and father were the only married couple in my neighborhood,” says Weeks, the principal of Pathways to Success Academic Academy.

As a result, his father was a father figure in the neighborhood, just as Weeks plays a similar role to many of the student’s of Ann Arbors’ Pathways to Success.

“My dad forged an unquestionable image in my life,” says Weeks. “He didn’t tell me how to live, he showed me and I learned from his example.”

Weeks says that while his father could be tough, he never doubted his love. And that’s a message he sends to the students at Pathways.

“One of the reasons I can hold students accountable,” he says, “is because they know I genuinely care about them.”

Weeks was honored this fall at the 13th Annual Celebration of Black Men sponsored by the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. Delta Psi Omega Chapter. The Celebration of Black Men was started in 2001 to recognize black men in Washtenaw County who have made a significant contribution to the black community.

Weeks was recognized for co-developing the Pathways to Success Academic Campus and for his past work with the development of the district’s Rising Scholars Program.

“People should know that Tyrone is very dedicated to this community and the success of students he comes in contact with,” said Patricia Manley, president of the sorority and an AAPS Board of Education trustee. “He has earned the right and deserves to be included in the list of education honorees.”

“I’m humbled,” says Weeks, 39, sitting in his office on Stone School Road. “When I was young, there was nothing that lead me to believe I’d ever be in the position to impact the lives of other people.”

Idyllic childhood

Weeks grew up in Detroit, the fourth of five children.

His mother prepared a home cooked dinner every night of the week and around the dinner table valuable lessons were taught. His father worked long hours for 35 years for Chrysler in Trenton, working as a hi-lo driver. Each morning he would leave for work at 4 a.m. to return home at 4 p.m. tired, but not weary.

“My dad loved to work,” says Weeks. “Work defined him, he believed that it shaped character. I learned my work ethic from my father, who was our provider and a protector.”

“There was a lot of love and compassion behind everything my parents did,” he recalls, noting that his parents have been married for 51 years and now live in their native Mississippi.

He says his happy, secure childhood meant he didn’t have to deal with some of the issues facing his friends.

“My father’s presence in my life was a deterrent from a lot of things, because I realized if I misbehaved in school or ever got in trouble, I would have had to answer to my father,” he said. “He had firm expectations for his all of us. There was a reverence in my house that we respected my dad’s presence, and the values my parents taught us.”

There were others in his life who helped make a difference, as well.

Weeks recalls cutting a class at Detroit Northern High School (Smokey Robinson was a graduate) only to get a knock on the door from Principal Marvin Youmans.

“He asked me, `What do you want to do?’ Did I want to be like a lot of other kids in the neighborhood, or did I want to utilize the skills I had and not just make a difference in my own life, but make a difference in the lives of other people a lot of other lives? He saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself. That visit had a huge impact.”

Juvenile corrections experience

After high school graduation in 1994, Weeks majored in secondary education at Eastern Michigan University, with a focus on history, English, and African American studies.

But substitute teaching made him rethink his career path, and after graduation, he worked as a youth specialist at the W. J. Maxey Boys Training School in Whitmore Lake for three years, and then spent the next three years in the probation department of the Washtenaw County Juvenile Court.

After so much time in juvenile corrections, he realized the importance of getting through to kids much earlier than the teen years, and decided to teach after all.

He started at Pioneer and Roberto Clemente, where Superintendent Todd Roberts (“an extraordinary visionary”) allowed him and counselor Victor Kennerly to begin a program in AAPS called the Rising Stars, in partnership with the University of Michigan’s Center for Educational Outreach to prepare underserved teens for the rigors of college.

The program continues today.

“Many of those students have gone on to graduate from college and have proven that—given proper preparation and support—all students have the ability to succeed in college,” he says, noting that during the holiday break, he ran into a former student now preparing for graduate school who expressed her gratitude for being in the Rising Scholars program, calling it “an unexpected gift.”

Weeks next became the 12th grade principal at Pioneer High School until budget constraints led to the elimination of that position after a year.

That led him to take a similar position at Plymouth High School, a job that involved supervising students and teachers at three high schools on one campus. It was so demanding, he knew at the end of the year that if he could make it there, he could make it anywhere.

When he heard about an opening at Ann Arbor Technical High School, he applied for and eventually accepted the position, and has been back with AAPS now for four years.

Pathways: Showing teens that education is relevant

Two years ago, Weeks and Dr. Ben Edmonson accepted the challenge to design and define a new program, merging Ann Arbor Tech with Roberto Clemente Student Development Center. The two were then co-principals last year before Edmonson became superintendent of Ypsilanti Community Schools.

“It’s been fulfilling because you can see something grow,” says Weeks, noting that the support of Superintendent Jeanice Swift and LeeAnn Dickinson-Kelly was essential to getting the program up and running.

Weeks soon came to realize the vast responsibility of making sure students graduate and understand how to overcome obstacles that reach beyond their control.

“We have to consider methods of connecting curriculum to the experiences of our students,” he says. “When we teach literature and talk to them about math and science, do they see themselves in the curriculum? Our focus must shift from solely from being concerned about the curriculum in which we teach, but instead about developing our students.”

Several principals over the years have mentored Weeks. From the late Joe Dulin, he learned about community building. Former Pioneer Principal Michael White, who has a military background, taught Weeks about organizational leadership and learning communities.

“I’d like to believe that I’ve taken some of the best of both principals, with some of my own philosophy as well,” he says.

Weeks lives in Ypsilanti with his wife, Stacia, a counselor at Skyline High School, and their two children. He is enrolled in a PhD program in urban education at EMU and can see himself at a college teaching future principals school leadership.

“It’s challenging, but right now I enjoy the work we’re doing here,” he says. “Fortunately, we have a great staff, and I can go up and down the roster and say that our faculty and staff are exceptional, and people here really enjoy working with each other.”

Weeks is excited about what’s happening at Pathways this year, especially the community partnership with Zingerman’s.

“The bottom line is that kids, when given the proper support and given the opportunity to see themselves in the curriculum are capable of great things,” he says. “Our students have to understand that what they’re learning is relevant to their individual experience, all kids can be scholars.”

Be the first to comment