Justice InDeed focuses on exposing the history of racist housing discrimination in the county

By Jo Mathis/AAPS District News

Several social studies classes in all five AAPS high schools recently have hosted teams of University of Michigan students talking about a topic close to home.

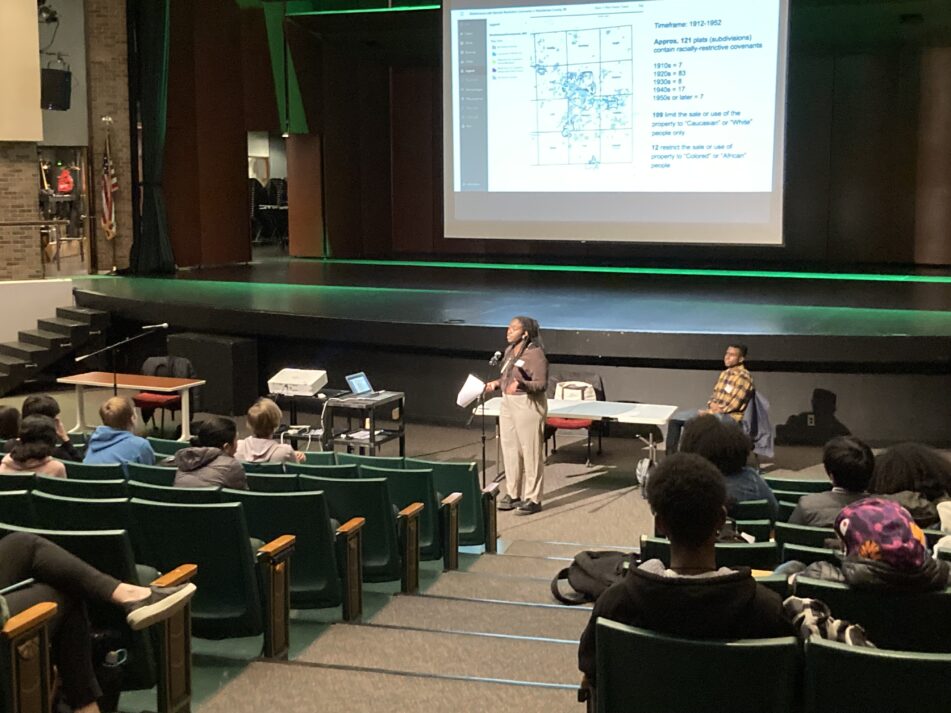

Justice InDeed is a collaborative project dedicated to exposing and responding to the fact that the deeds to thousands of homes in Washtenaw County contain “racially restrictive covenants” – or provisions prohibiting Black people and other minorities from living there.

A research project at the University of Michigan, Justice InDeed focuses on exposing the history of racist housing discrimination in the county, mapping the subdivisions and homes whose deeds have contained racially restrictive covenants, and encouraging future reparative housing policy.

The presentations at AAPS high schools have been led by members of Justice InDeed’s Education Subcommittee, including individuals from U-M libraries, Law School, and undergraduate LSA.

Hillary Poudeu Tchokothe, who graduated in May of 2022 from Pioneer High School, returned to her alma mater recently to talk to an African American Humanities class to inform the students about racially restrictive covenants (RRCs) and their impact.

“I started working with Justice InDeed during my senior year of high school and thought their work was interesting,” recalls Hillary, a University of Michigan political science student who plans to go on to law school. The fact that a group of professors, college students, historians, and community activists are all working together to teach local history that has never been taught motivated me to join this project.”

She explained that Justice InDeed not only works to educate the community on RRC but works on mapping so people can see if their neighborhood has any RRC. It has already helped one local subdivision repeal its RRC.

“I hope these presentations don’t just educate high school students more about local history, but also encourage them to work on projects that work to better the community through education and action,” she said.

Jared Aumen, who coordinates the district’s middle and high school social studies departments, explained that during the presentations, students voiced various reactions, including shock and disgust at the language in deeds and motivation to find out more about how widespread such covenants were locally.

“The project and its presentations provide our district social studies department a very real opportunity to reflect on local hard history, to engage in the work of mapping this past, and to consider how our civic society should respond to our history,” he said. “Collaborating with Justice InDeed exemplifies our orientation toward using academic disciplinary work in our pursuit of equity.”

Pioneer social studies teacher Kelly Czajka says that by the end of the presentation to her African American Humanities class, her students understood the importance of being able to strike language from deeds/historical documents.

As far as class presentations in the future, she suggests the leaders prepare resources for kids that explain some of the terms used: title, deed, and process of buying a house so that they have basic information going in, as well as a brainstorming session built into the class asking them to suggest or infer what the results would or should be as a result of this massive project.

“I think this could be a great way to get kids involved,” she said.

Aumen says the district’s social studies department is excited to consider how to create curriculum resources that support learning and action about the local history of racially restrictive covenants.

Be the first to comment