Mitchell modular classroom spaces represent more than innovative classroom design—they’re part of a larger vision that supports student readiness, positive behavior, and collaboration.

At the start of every new school year, elementary teachers across Ann Arbor Public Schools once again face the age-old question: How do I set up my classroom space?

But this year, something fundamental has shifted. The conversation is no longer just about arranging desks in neat rows or creating teacher-centered spaces. Instead, it’s about designing environments that truly serve learners—spaces that amplify student belonging, inquiry, creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and accessibility.

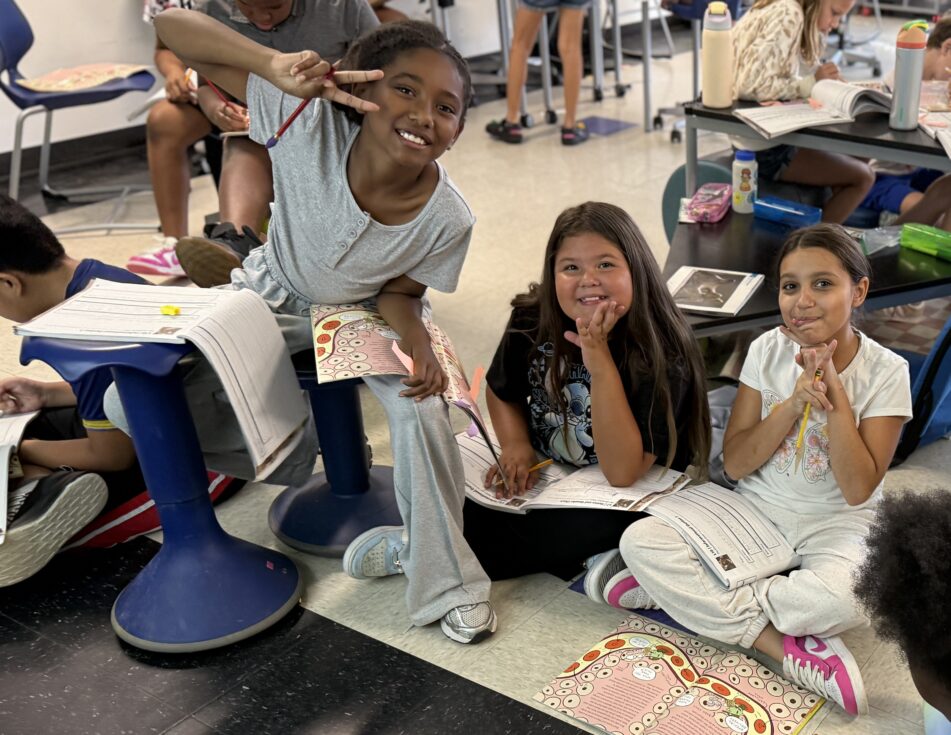

At Mitchell Elementary, Katie Gibson-Dameron, Elementary IT Consultant for Ann Arbor Public Schools, stands in the “Mitchell Module”—an innovative three-room suite that serves as more than a classroom.

“The thought process behind creating these spaces mirrors what could happen at the new buildings,” Gibson explains, referring to AAPS’ current construction projects. “And so it’s truly like a test-driving space.”

Two years ago, these were traditional classrooms separated by solid walls. Today, they’ve been transformed into a flexible learning environment featuring two fourth grade classrooms connected by a shared collaborative space—a design that previews the innovative architecture coming to AAPS’ new elementary buildings.

AAPS is currently constructing new buildings to replace Mitchell, Dicken, Logan, and Thurston elementary schools.

The Collaborative Heart

The shared flex space between the two classrooms serves as the heart of this innovation. Students flow naturally between rooms during workshop time, and the space can accommodate everything from small group work to co-teaching opportunities to grade-level meetings.

“Students will come in here, and they just flow right in,” Gibson says. “They had a conversation about expectations and what it looks like, sounds like, and feels like.”

The possibilities are intentionally endless. Both classrooms can use the space simultaneously, teachers can co-teach with content projected across all three rooms, or the space can host collaborative projects that bring together the entire grade level. It’s a model for the kind of flexible, adaptive learning environments that will define the new elementary buildings.

Gibson says the two fourth-grade teachers—Londyn Swenson, who is new this year, and Scott Arrowsmith, who is in his second year at Mitchell—have been quick to embrace the new possibilities.

“It’s been nice to have a lot of choice in the way we set up our desks and set up our seating,” says Swenson. “And the flex room—even though we haven’t had a ton of opportunities to use it as the beginning of the year— it’s been really nice to have a space for our students who might want to work in a quieter setting—and I can still see them right there. Or for groups more scattered out to have more space.”

Beyond Furniture Arrangement: Creating Conditions for Learning

Walking into Scott Arrowsmith’s classroom, the intentional design becomes immediately apparent. Gone are the traditional rows of individual desks. Instead, the space flows outward from a central gathering area where students can choose to sit on the floor or quickly form circles by turning chairs to face each other.

“He’s kind of built his space out from that,” Gibson says. “But in his process, he’s going to ask the students in a couple weeks, what’s been going well, what do we need to change? I’m gonna ask you to give me feedback on the space, right?”

This student-centered approach to space design represents a fundamental shift in thinking. Rather than creating static environments that remain unchanged throughout the year, these educators understand that effective learning spaces evolve based on student needs and feedback.

In Swenson’s classroom, collaboration is built into the very structure. Triangle tables are pushed together to seat four students, creating natural partnerships and group work opportunities.

Supporting Pedagogical Innovation

The transformation goes beyond furniture—it’s about enabling new ways of teaching and learning. Gibson’s role has evolved from instructional technology consultant to a broader focus on space, pedagogy, and technology. How can classroom design support sharing structures like those in Arts and Letters—mix-and-mingle, gallery walks, and discussions? And how can we build purposeful partnerships so these structures become seamless, helping students feel confident and comfortable learning together?

The connection between space and pedagogy is crucial, she says.

“We’re seeing all of this exciting pedagogical shift, but the classroom environment needs to evolve alongside it to fully support these changes,” Gibson says. “For example, if each student has their own table, it can be challenging to create space for activities like mix-and-mingle, where movement and interaction are key.”

Choice, Flexibility, and Student Agency

One of the most significant aspects of this transformation is the emphasis on student choice and accessibility. Traditional gathering spaces, like carpeted areas, are being reconsidered through the lens of learner variability.

“When they get older and you have that gathering space, they don’t fit in that space anymore,” Gibson notes. “We also know our neurodivergent students. They need to have a choice. If we’re constantly saying, like, community is on this carpet, you sit to build community, you look at me to build community. The first thing those students want to do is look at the door, ‘How do I get out of here?’ Because this is uncomfortable. It’s too close, it’s too loud, it’s too much.”

Instead of mandating that all students participate in the same way, these redesigned spaces offer options. Students can engage from different positions and proximities, ensuring that learning is accessible to all. This approach recognizes that true community building happens when every student feels comfortable and included.

Preparing for the Future

As AAPS prepares to open new elementary buildings, the Mitchell Module serves as both a prototype and a proof of concept.

“My hope is, for instance, in a couple of months, administrators can hold a staff meeting here and kind of get a feel for what this looks like,” Gibson says.

While not every building in the district can immediately replicate this model due to design plans and space constraints, the lessons learned here are informing district-wide conversations about classroom design.

The new buildings will feature collaborative spaces, flexible furniture, and coat rooms—all elements being tested and refined at Mitchell. Most importantly, they reflect a shift toward designing classrooms that support how students learn best, creating environments that are adaptable, inclusive, and engaging.

Gibson emphasizes that setting up a classroom space is not a one-time event but an ongoing process. “It’s not like you come in and everything’s exactly where it’s going to be for the entire year. It’s always a process of what could be changed, but I think one of the things we miss the mark on is asking the kids: What is working well? What is helpful to your learning? What makes learning hard?”

She says the work is about “setting the conditions for learning, not just arranging furniture.”

Be the first to comment