About 540 students are enrolled in ASL classes in Ann Arbor Public Schools

By Jo Mathis/AAPS District News

When AAPS American Sign Language teacher Jennifer Niner heard about the movie “CODA,” she knew she wanted to see it alone.

As a hearing CODA (Child of Deaf Adults) herself, Niner knew it would be an emotional, tearful experience.

It was. All twelve times she’s seen it.

“I honestly feel that movie was my whole life!” says Niner, who teaches ASL at both Pathways and Community high schools. “I watched it by myself first because I knew I was going to be a hot mess. I cried my eyes out and laughed. Then I watched it with my husband and my mom, and she said, `This is your life!’ I said, `Yes, I just wish I could have sung as well as the lead character did.”

She’s shown “CODA” —which is streaming on Apple TV—to all of her students.

“I want everyone to see it, and I hope people who do really understand deaf culture; that most deaf people really love their language and they love their culture and they love for anybody to experience ASL—even if it’s just 20 or 30 signs. Just acknowledge that they’re just deaf. They’re not disabled.”

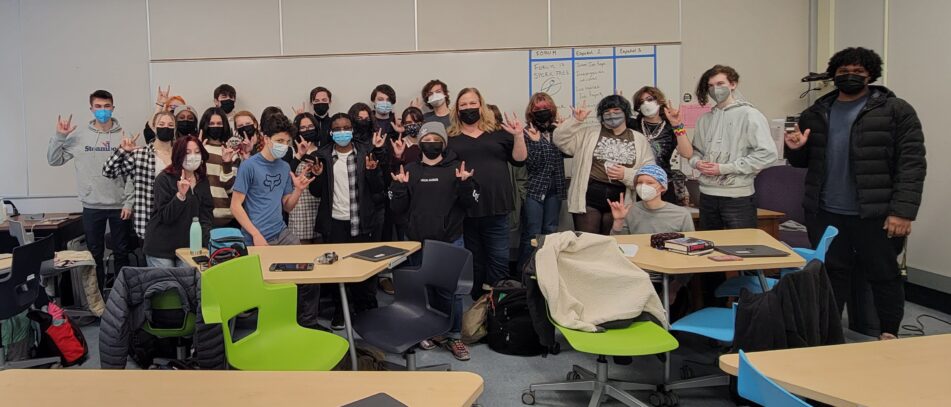

About 540 students are enrolled in ASL classes at AAPS high schools and Scarlett Middle School.

The district employs four ASL teachers, one of whom splits her time between one class at Huron High, and Scarlett.

Community High School students: Happy to take four years of ASL

Community High School student John Umbriac knew nothing about ASL before signing up four years ago.

“The concept of a visual language seemed interesting, but I mostly decided to join because it was the best option of those available,” John says. “I am very glad I did though. I’ve always struggled with foreign languages, but ASL has an aspect of creativity that makes it rewarding to keep learning. In addition to that, the decision to take four years of a world language is a commitment as you only need two. With Jen’s teaching style it was an easy decision.”

CHS senior Leah van der Velde says they knew next-to-nothing about the Deaf community before signing up for ASL, and notes: “It was, to me, an untouched subject and language, which made it that much more important to learn. Almost everyone in my family was confused about why I wanted to take ASL because I’m probably not going to encounter that many deaf and hard-of-hearing people in the world. But deaf and HOH people probably don’t encounter that many hearing people who know how to sign. So when it does happen, and I can sign to a deaf person, I know that’s going to be such a special moment for both of us.”

TJ Watson initially took ASL because he didn’t want to take Spanish, adding: “It’s harder for me to learn spoken languages and so ASL being a very ‘hands on’ language was something I took interest in. Also being partially hard of hearing makes me feel like I connect to the language a bit more.”

“I am 100 percent glad I took the language,” TJ adds. “I use ASL outside of class with my brother and boyfriend, and my mother and stepfather are learning ASL as well. Family dinners are partially signed with me being the most experienced which is weird yet kinda cool. It’s especially great in louder settings to be able to still talk to my family and partner when I can’t hear them, we just switch to ASL and continue doing whatever we’re doing.”

All three said they loved the movie “CODA.”

Career path to AAPS

Niner grew up in Dearborn Heights, the only child of deaf parents who learned American Sign Language before she could speak. At three months, she signed “Mom” and by the age of one knew about 20 signs.

Learning English was never a problem because she lived so close to extended family, all of whom were hearing, and she learned from friends and neighbors.

Though her parents—Stephen and Barbara Post—each read lips and spoke well, Niner was the only one on either side of the family who knew how to sign, which meant she was the family’s one and only interpreter.

As a CODA, she says, she grew up fast.

“I was interpreting doctors’ visits at seven- and eight years old, and definitely in very uncomfortable situations just like in the movie,” says Niner. “Stuff kids don’t want to talk to their dads about. I’ve advocated for my parents since the age of nine—for interpreters, for equity, equality for their jobs, being taken advantage of, discrimination.”

She said in her late teens, she briefly felt she’d been robbed of a normal childhood.

“And then I grew up,” she says. “I went to college, and I realized this is exactly what I want to do. I want to teach deaf people. I want to expose this language as much as I possibly can.”

After college, she worked as an interpreter at Pioneer High School for a few years before working as a Deaf Education teacher of deaf and hard-of-hearing students. After that program transferred to the Washtenaw Intermediate School District (WISD), she worked at Bryant Elementary with a mainstreamed Deaf child for a few years.

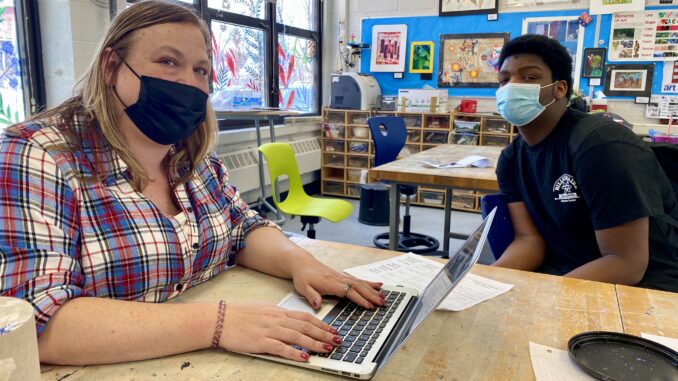

For the past eight years, she has been an ASL teacher at Community and Pathways high schools.

She applauds Brooke McCully ASL Teacher at Pioneer whom she worked with for seven years in the Deaf Ed program for pushing for ASL as a Foreign Language in Ann Arbor.

“She did a lot of the hard work by writing the program and getting it approved by the state,” she says of the Pioneer High School ASL teacher.

Niner also admires the work of ASL teachers Lisa Gapa, who works at Scarlett Middle School and has one class at Huron High School, and Cait Feasel, who teaches at Skyline High School.

Between 250,000 and 500,000 people of all ages throughout the U.S. and Canada use ASL as their native language, Niner noted, added that ASL is the third most commonly used language in the United States.

“For me, the movie opens people’s eyes to the beauty of a language that can be done with your hands,” she says, “and that anybody can learn it because it’s such a visual language. We don’t have as much conjugations. It’s just a language you learn with your hands., and it’s so popular right now in Michigan.”

Niner says wearing masks during the pandemic has naturally been difficult for the Deaf, especially those who depend on lipreading. It’s also been hard for her younger students to understand her sense of humor because she relies so much on facial expressions. Clear masks are available for anyone in the district who has hearing loss and needs to read lips.

Still, she says, her students’ signing is “phenomenal.”

One thing students soon learn about her is that she is very blunt, and she says she gets that from her parents, who tend to think in terms of black versus white, with little gray in between, partly due to the nature of sign language.

“I always tell students, ` I’ve got parents who are like `what you see is what you get,’ and I’m just that type of person, too,” she says. “And I think it takes some of the kids a little a little while to get it but then once they realize who I am, they will love me for that.”

Niner lives in Dearborn Heights with her husband of nine years, Russell Niner (who lost hearing in one ear after contracting meningitis when he was two), and her widowed mother, Barbara, who lost her husband to cancer 10 years ago.

Niner recalls that when she was growing up, people would sometimes ask ignorant questions about her parents, and Deaf culture. She’d be angry, but her father would always encourage her to give others the benefit of the doubt, to offer grace, and always look for the good.

So her attitude softened, even as she never stopped being a defender of her parents.

“I feel my whole life has been peer advocation,” she says.

Despite the many times it was hard being the only child of two deaf parents—largely because of the responsibility of interpreting in public and at doctor appointments—she wouldn’t change a thing.

“There probably were times in my life where I was like, ‘Why me?’ But now I think: This is my life and I love my life and I would never go back to change it. I’m proud of who I am. I’m proud of my parents. I’m proud of the Deaf community. It’s just so finally nice to see them portrayed in a way that they should be portrayed.”

Be the first to comment