Story and photos by Jo Mathis/AAPS District News Editor

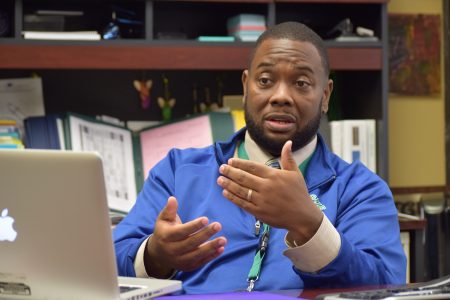

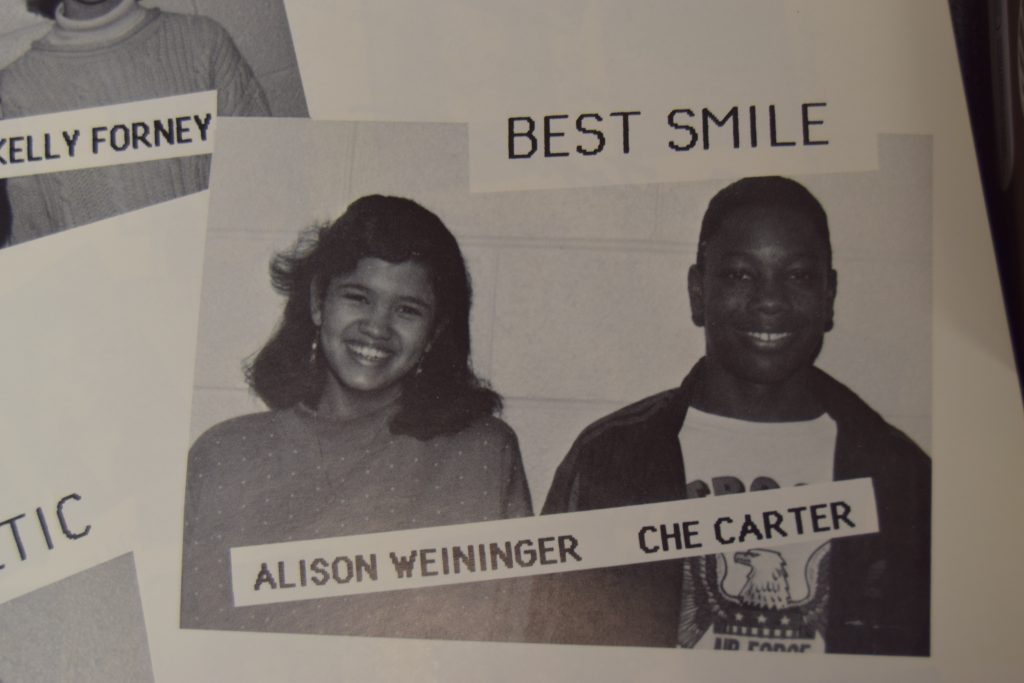

When Clague Middle School Principal Ché Carter was a junior at Huron High School back in 1992, a teacher suggested that he belonged on stage.

In fact, she said he would make a great Wiz in an upcoming production of “The Wiz.”

Though Carter had never even considered such a thing, he agreed, with one caveat: He would absolutely not under any circumstances sing.

And so when the curtain rose on that production, the charismatic Ché Carter was indeed the Wiz. He was the Wiz who rapped.

“I liked to do things my way,” says Carter, 42, sitting in his office at Clague, where he was a student 30 years ago. “And sometimes that got you into trouble. Especially in high school.”

Carter, 42, was recently named the 2016 Michigan Elementary and Middle School Principals Association Region Honors for Region 2, which is based on teaching/administrative experience, participation in professional and civic organizations, and advancing the profession through service.

Few in Ann Arbor Public Schools were surprised.

In fact, when LeeAnn Dickinson-Kelley first met Carter, he was graduating from Eastern Michigan University with his teaching certificate as EMU’s Most Distinguished Young Educator of the Year.

“A few minutes into the conversation, I knew I had to recruit him as an Ann Arbor Public School teacher,” recalls Dickinson-Kelley, assistant superintendent for Instruction & Student Support Services. “Some people become leaders because of opportunity, some because of hard work, some are just naturally born to take on the mantle of leading and changing the world from the inside out. Ché Carter is all three. He is one of the most remarkable educators I’ve had the privilege of knowing during my career.”

Lifelong Ann Arborite

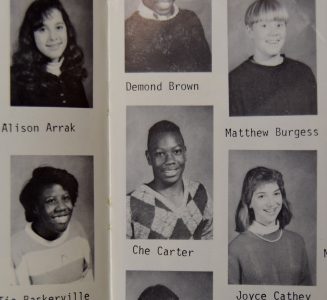

Ché Carter was born and raised in Ann Arbor, the middle of three brothers who are still best friends to this day.

The family lived in the Arrowwood Hills co-op about a mile’s walk from Northside Elementary.

Carter’s mother Lucindia Shelton was a teacher’s assistant in AAPS for all the years her sons were in school. She would go on to graduate from Eastern Michigan Unversity a year before Ché graduated from EMU, and retired two years ago from AAPS as a special education teacher.

“She was always giving, putting others first,” says Carter. “Now all three sons are the same way.”

Carter’s father, Leroy Sr., was a member of the Black Panthers who named Ché (pronounced “Chay”) for Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, and his youngest son Cinque Joseph for the West African who led a revolt on a Spanish slave ship.

“We were always taught to be very strong and courageous; to stand up for what we believe in; to have lots of integrity and be men of character,” says Carter, noting that his father taught self-pride, not a dislike for other races.

Though his father made sure there was plenty of literature about successful African Americans in the home, the same could not be said for the collection at school, Carter says.

“If you don’t see yourself reflected in all these things around you, then how do you aspire to be something more?” he asks. “It’s hard to understand other people if you don’t know about yourself. If you know about yourself, you can pretty much stand strong and represent yourself in a way that shows appreciation for other cultures as well.”

His parents separated when he was five. To this day, Leroy Carter, a field service representative for Michigan American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees Council 25, is his son’s “moral compass.”

Carter’s move to Clague Middle School in the seventh grade was eye-opening because the school was a melting pot for the Northside kids who were predominantly black, and other feeder schools which were mostly white.

Co-principal Gary Court, who is now principal of Angell Elementary, recalls that Carter had exceptional interpersonal skills.

“Ché was perceptive about others,” says Court, “and had keen insights and good intuition about relating and getting along with both classmates and adults.”

About that time, rap was introduced to the music scene and Carter took to it naturally.

“Rap was a way for the powerless to have a voice,” he says. “It was really about reporting what we saw every day. But there’s also the sense of the struggle – trying to get out of your situation, your poverty, your deprivation. The spoken word was powerful.”

While he had no trouble being accepted by his peers, he got in trouble a lot because he was quick to speak his mind in class.

“That’s your defense mechanism to say, `Hey guess what? You may smash me with your teacher power. But I’m going to take it back by making you mad and taking your class in another direction. So I’m going to say something funny.’”

Hence, he spent his share of time in the detention room—space that is now his office.

Once Carter got to Huron, he joined fellow students that included his older brother, LeRoy, who was captain of the varsity football team, as well as an uncle and cousin.

Happy to be one of “the Carter boys, ” he enjoyed football, track and field, and rapping as the Whiz.

But he had an attitude. Sometimes he didn’t feel like going to class. And when he did, he was prone to speaking his mind—especially when he thought something wasn’t true or fair, or when he felt the need to stick up for someone.

“There was a lack of engagement,” he says. “There was nothing there that made me feel connected at the time. I felt like the teachers were only trying to help the kids who already got it, or the kids whose parents were already involved in the school. It felt like the Arrowwood kids were a second thought. Kids know. Kids know when they’re not valued. Kids know when you’re watching them a certain type of way. “

Some teachers back then didn’t value the talents and gifts African American students brought to the classroom, he says.

“So if I’m outspoken, instead of writing me up for speaking out of turn, why don’t you give me an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the classroom?” he says.

“You give me an assignment and tell me to read this page, and I give a perspective of my own. If a teacher devalues that perspective, you just made me look small in front of my peers. But professionals are supposed to validate the discussion. When the world constantly reminds you over and over again that you’re different, you tend to want to push back. So the only power you have as a student is to take the class off track.”

In 1991, Carter was sent to Roberto Clemente Center, where the alternative school’s weekly rap sessions made a huge impression—even if he did more listening than talking.

When Principal Joe Dulin told him he’d end up in prison if he continued disrespecting authority, Carter assured him he was wrong.

Then came the night his brother was injured in a drive-by shooting.

“When you see something like that, you automatically want revenge,” he says.

But during the rap session following the shooting, Dulin told Carter he was proud of him for coming to school on that difficult day.

“A lot of people who talked to me that day reminded me of all the opportunities that were ahead of me if I just did not get into that street life,” he recalls. “Roberto for me was about putting my priorities in place and applying myself.”

So he returned to Huron for his senior year and got on the honor roll. After graduating in 1992, Carter considered going into the Air Force until he learned his asthma would prevent that. So he enrolled at Washtenaw Community College with a plan to major in mortuary science.

“My thought was: People need somebody who can be good to people in their worst times,” he says, noting that a counselor talked him out of it by insisting he had a lot more to give to the living.

In any case, he was more focused on the music business and his hope to make it as rap artist. He went to Atlanta with fellow artist and friend Fernando Payne, created a production company, and ended up getting signed to a label with songwriter Barrett Strong.

“School was the backup plan,” he says. “Two classes here, two classes there. Working as a custodian at Huron at the time. Working for the city of Ann Arbor’s canoe livery. I worked at U-M in MRI as a tech assistant.”

When he got a job in before and after school childcare at several AAPS elementary schools, Carter realized how much he enjoyed working with kids.

And in 1995, while attending the Million Man March in Washington, he experienced a “moment of awakening.”

“The charge was to go back to your community and do something powerful,” he says. “When I got back to Ann Arbor, I said, `OK, I gotta take care of business.’ I started taking more classes and more classes. The whole idea was that it would pay off at some point.”

Focused less on the music industry and more on a career in education, Carter enrolled in classes at Eastern Michigan University in 2000 and was encouraged when a teacher told him there were kids out there who needed him and were waiting for him.

Meanwhile, he was taking 20 credits, working 40 hours a week at U-M, and 20 hours on the weekend for the city of Ann Arbor.

And in 2002, he welcomed a daughter, Avani.

“You ask me how I did it? I just know it couldn’t be done again. But I did it.”

A return to AAPS

Carter loved student teaching in Willow Run. But his heart was in his hometown, and when he heard about an AAPS job fair, he waited in line for three hours to apply.

“Because I had such an interesting time in the district—with highs and lows and missed opportunities—the best way to fix something is to be in a position to have an eagle eye on the operations and then figure out how you can help people have a better experience in the school system,” he says. “So I got into it for all kids, but I definitely know there’s a group that seems to constantly come in last in all of our data. My philosophy was, `I can help them change. But I’m going to need the community to change how they feel about this other community.’”

He taught first and second grade for four years at Bryant Elementary.

Dickinson-Kelley says she closely followed his early teaching career and knew he was destined for even more.

“His innate leadership,” she says, “unwavering commitment to issues of equity, deep care for children, his understanding of effective instructional practice and remarkable manner with adult colleagues are the qualities we seek for building leadership.”

One of the best things he’s done at AAPS, Carter says, is to work with struggling students during the summer, teaming with staff from across the district.

“I can say confidently that we have some of the best people – not just educators – but best people working with our kids,” he says, referring to the summer staff. “It almost spoils you because you get together with these teachers every day and they call each other on the phone constantly trying to figure out: How can we change what we’re doing to better educate the kids we serve?”

Burns Park Elementary Principal Chuck Hatt recalls that in one of Carter’s first assignments as an administrator for AAPS, he served as principal of the district’s elementary Summer Learning Institute.

That summer, veteran teacher Elnora Sipp was on staff to work with second graders.

In fact, she had been Carter’s teacher years before.

“When greeting and working with Ms. Sipp throughout the summer,” Hatt recalls, “Che was always the deferential former student and equal partner in working for our most vulnerable students. He was able to be both as he knows from personal experience how committed educators make an everyday difference in lives of children and he has committed himself to nothing less in his own professional life and in the work of the teams that he leads.”

Hatt remains a huge fan.

“Mr. Carter is the embodiment of our mission for excellence and equity in service to the children of Ann Arbor, their families, and the institutions that support them,” he says.

Carter knew that as a teacher he could create an environment of respect where every student values the other students’ perspectives and what they bring to the table, but as a principal, he could do more for more students.

So he became an assistant principal at Forsythe Middle School for two years before becoming principal at Pattengill Elementary. Four years later, he was tapped to lead Clague.

“All kids want to be heard”

Since Carter has been at Clague, the school has moved to a new grading system based on standards, so that letter grades now have a better-defined meaning.

“I can say it’s really changed the way kids look at learning in middle school,” he says. “They know what an A means. They know what a B means. Why? Because every activity is aligned to a particular standard they have to meet so many standards, and that hopefully transcends into some of the data we get.”

Clague has always been a high-functioning community as far as academics, he says.

“But to me, there’s so much more than academics in the development of young people,” he says. “And so yes, we’re still proudly trying to lead the way in academics. And we’re in the process right now of trying to be identified as a Schools to Watch program, a national program very similar to Blue Ribbon but for middle school.”

“All kids have the same needs,” he says. “They want to be heard. They want to be supported … They don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care. And that’s been a cornerstone to my leadership style. You’re going to know I care about you. I’m going to demonstrate that in everything I do.”

He says teachers these days are more aware of the importance of shared respect, and choose their words more carefully.

“I think the biggest difference now is that kids feel entitled to the same level of respect as adults,” he says. “So we’re constantly teaching that respect is earned. That’s why you have a lot of programs now like PBIS—Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports—where you teach the expectation that you want and you reinforce that in every zone in your school. So at least you have a common vocabulary around the norms of this environment.”

Clague parent Shanti Suresh says the thing she finds most impressive about Carter is that he is so fully engaged in all aspects of the school.

“His emails are very sincere and heartfelt,” she said. “I take the time to read every one of them, and I can tell he cares about the kids because the emails have so much depth and information in them. “

She said Clague kids are fond of him, as well.

“He comes up with new ways to connect with them and get his message across,” she said. “He is doing wonderful work with the Clague kids, teachers and parents.”

Clague’s African-American population is just under 12 percent.

“I have a very diverse population, and cultural competency is key,” he says. “One of the things I pride myself on is that I can go into any environment and be successful and raise the bar based on me being culturally competent and understanding the nuances coming from a sub-group or sub-culture, and understanding how important it is to honor other people’s cultures and what they bring to the table, and what they bring to America. Just because they come from another country doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t have American values.”

Goal for Clague: a caring, cooperative community

Carter’s administrative assistant, Laura Hannaford, says Carter has created a joyful environment at Clague that radiates throughout the building.

“Every morning we do announcements,” she says, “and he reads: `Do your best to make Clague a caring and cooperative community. Be respectful, responsible, safe, and caring.’ He asks that of everyone, and he does that every time I see him interact with someone, whether it’s a parent or a student.”

She says the kids know he cares by the attention he gives them.

“It goes to being with the kids when they’re having fun as well as in-class learning,” she says. “He’s in the lunchroom all the time with them. He sits down, he talks to them. He knows what they’re doing on the weekends. He goes to some of their games, their sporting events, their music events. He’s just part of their lives for all of it. And people respond to that.”

Carter tries to be the mentor for young people that the late GM engineer Dr. Frederick Mccuiston was for him when he was a boy and young teen.

Because some parents don’t feel comfortable coming into the school, Carter goes to them when necessary.

Recently a mother felt her child was not being treated fairly by a teacher. So Carter went to the home, where he would not be seen as the one with authority, and resolved the issue at her kitchen table.

“I need to look away from policy at times and look at the needs of people,” he says. “And by doing that, people let their defenses down long enough and tell you what the real need is.”

An Arab American parent was at school before break to pick up his sick child. Carter could tell there was more on his mind, so he gave the father a few times he could come back and talk.

The father was en route to his car when Carter decided to arrange his schedule and talk to him right then. He’ll always be glad he did because the father was worried about his son and “Islam phobia.”

“At the end of the day, every parent wants their kid to feel safe, and we know that there’s so much going on in the world, we can’t guarantee safety,” he says. “We can guarantee a response. We can be prepared. But we can’t guarantee safety. That’s not a luxury we have. We never did.”

He says he could tell the father felt relieved to know his concerns were heard and honored.

“My job is to show students how they can maintain their identity in this environment and still be who they are,” Carter says. “My job is to help teachers understand that it’s a difference perspective, not a deficit perspective because you don’t understand the context in which some kids operate from. Knowing their music, knowing the things that make them excited. Why should we look at that as less? Why are the non-dominant cultural references usually looked upon as a deficit? So my job is to show kids how you can favorably assimilate and stay who you are. But you assimilate like everyone else does so you can be in the game. But you can’t be in the game if you don’t know how to assimilate.”

The hardest part about being principal, Carter says, is the fact that it’s all-consuming, which is why he’s sometimes awake at 3 a.m. reflecting on how he can better support a teacher or a student. Lately, he’s especially concerned about the mental health of young people.

On the flip side, he loves seeing the look on kids faces when they feel included; the comfort in their eyes when they engage as a leader; the appreciation from parents who’ve watched their children excel in ways they didn’t know they could; and the appreciation of a teacher who has just learned a new tool.

“We’re highly skilled professionals, but guess what?” he asks. “We have to keep retooling. We have to keep changing. It’s not like any other field out there. We have the opportunity every day to make an impact and change someone’s life. We touch the future every day. And every day I get to reinvent myself and be somebody different for another child.”

Adults should never underestimate their impact on a child, he says.

“And please don’t judge a child by how they act in middle school,” he says. “Because if you judged me by the way I acted in middle school, you wouldn’t say I’d be this principal trying to change the world one person at a time. “

“Servant-leader” feels called to serve Ann Arbor families

He and his wife, Angelique, a former dental assistant who is now a fulltime homemaker, have two children, Ashon, 9, who attends Carpenter, and Avani, now a freshman at Community High.

A move may be in store for the Carters. After all, he’s coming to that four-year timeline when he gets restful to move on.

“I’d like to lead an international school,” he says. “I’m curious what that would look like outside of the United States.”

He pictures moving out of the country for three to five years before moving back to AAPS, possibly someday as superintendent.

In the meantime, he knows there are still several principals and teachers in the district who remember him when he was a stubborn student who put up walls when they tried to get to know him; who sometimes made bad choices.

He hopes they feel proud of him now.

“Hopefully they look at me and it inspires them to know that there’s hope for every kid,” he says. “Looking at me, you wouldn’t have said, `Hey, I’ll see you pretty soon. You’ll be a principal.’”

Carter sees himself as a “servant-leader” called to serve Ann Arbor families.

“I’m a hometown kid,” he says, “and now I’m just looking at one thing: How can I best serve more people?”

I first met Ché during our Summer Learning Institute when he was still a teacher. I was impressed with him from the start. He was so hard working, so dedicated, and so obviously motivated to do the best he could for our students. He is an outstanding educator, and a wonderful person. I am so proud to have worked with him, and so glad he is leading Clague School.

I first met Ché during our Summer Learning Institute when he was still a teacher. I was impressed with him from the start. He was so hard working, so dedicated, and so obviously motivated to do the best he could for our students. He is an outstanding educator, and a wonderful person. I am so proud to have worked with him, and so glad he is leading Clague School.

Proud of you then! Proud of you now!

This award could not have been given to a more deserving individual. Congratulations.! When I asked Ché, “Why do you want to leave the classroom?” He did not give me the pat answer one would have expected, “I want to make more money.” He said that he wanted to get in a position where he “could help more students succeed and in a position where he could influence educational policy to make that happen.” It seems that he is well on his way to accomplishing both.

This award could not have been given to a more deserving individual. Congratulations! When I asked Ché, “Why do you want to leave the classroom?” He did not give me the pat answer one would have expected, “I want to make more money.” He said that he wanted to get in a position where he “could help more students succeed and influence educational policy to make that happen.” It seems that he is well on his way to accomplishing both.

He was a great guy during my years of playing football with him! Doing good things oldschool!

We miss him at Forsythe!

Our daughter has been so blessed to have had Mr. Carter as her principal in elementary and middle school. He exudes absolute dedication to his students and their families. AAPS is lucky to have such a wonderful educator and leader, as are we!

Thank you and congratulations on your well-deserved distinguished honor Principal Carter, for seeing Donald D3 Poole as a 7th grade student that happens to be disabled and special.

He is learning and included in your village of student body.

Ms. Marcia Boik is Donald’s teacher reflective of your continued Leadership.

The best of luck to you and your family’s future journey.

Sincerely,

Aafrika Mom

Mr. Carter would come to many of the baseball games that his students were playing in when he was at Pattengill. This made a huge impact on the kids because he took time out of his personal schedule to support them. My son is now a senior and still remembers Mr. Carter with fondness.

Four out of five of our Ann Arbor grandchildren have had the privilege of attending the Clague Middle School, so ably led by Che Carter. The fifth will enter sixth grade next fall, and we feel confident that he will benefit enormously from the experience too, as it is such a loving and caring place.

Sincerly, the Baker Lexington, MA grandparents.

Congratulations, Che Carter! Clague MS and the AAPS are so lucky to have you! This is a well-deserved honor.

Che, Mary (Davidson) and I are so proud of you!

Last year, Ramadan overlapped with the last days of school, and I told Mr. Carter that I would be fasting those days. He let me skip Gym, so that I wouldn’t get thirsty throughout the day, and go to Orchestra instead. He also let me not got to the lunch room, so I wouldn’t be watching people eat when I can’t eat myself, and he let me go sit in the blue house and read a book instead. So overall, he let me have the easiest days of Ramadan, even better than when I’m at home and everyone is fasting, by taking it easy, and being busy at the same time, so I wouldn’t even think about being thirsty or hungry. Thank you, Mr. Carter.

I directed Che’ Carter in the production of The Wiz at Huron High School and can recall how stellar he was in the audition. His energy was infectious, but he did not want to sing. I was curious if he could rap, and rap he did. He made it cool for other boys to perform in musical productions. Always a leader. Glad to see he became one in education. Bravo!